On the 9th of March, a country-wide theatrical release of PUSH took place all over Mexico!

Full cinema halls in Mexico City, Guadalajara, Tijuana, Cuernavaca, and elsewhere in Mexico were followed by enlightening conversations and Q&A sessions after the screenings.

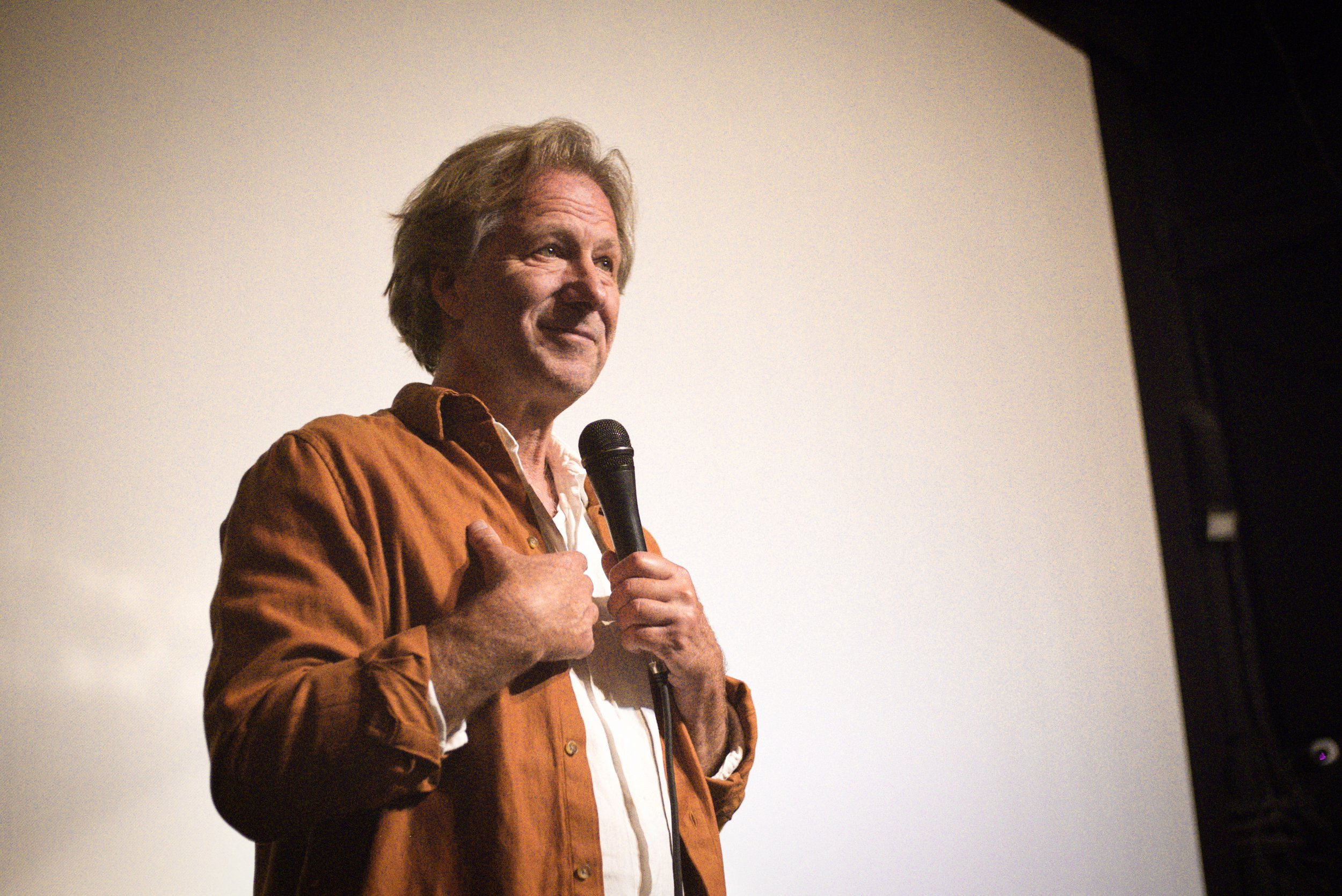

During weeks of screening, the cinemas and audience have been wonderfully welcoming to PUSH and its Director Fredrik Gertten. And although he is back in Malmö now, the film and its ideas continue an exciting journey through cinema screens, media channels, and on PUSHBACK Talks.

Below, we prepared a brief summary of the journey PUSH has had in Mexico, together with some captured moments from it.

Already three years after initial premiere of PUSH, the success and attention that PUSH has received in Mexico could not be predicted. In the light of a rapidly changing housing situation around the country, film has proved to be very relevant and interesting to the Mexican audience. With the Film Director Fredrik Gertten being present at most of the screenings, interesting discussions, meetings and Q&A sessions took place.

Right before the premiere in Mexico, Fredrik Gertten and Leilani Farha discussed the housing crisis in Mexico with 4 activists and experts in housing!

During his time in Mexico, film director Fredrik Gertten was invited to take part in the Debate programme on CANAL 22. Watch the full recording here!

Co-creators of PUSH and PUSHBACK Talks, Leilani Farha and Fredrik Gertten have weighed in on the housing crisis in Mexico in their latest opinion piece published on the Washington Post.

Read Fredrik and Lelani's Op-Ed "Gentrification isn't behind Mexico's housing crisis. Financialization is." here. You will find an English version here.

All episodes of PUSHBACK Talks can also be found on your favorite podcast apps and streaming services such as iTunes, Google Podcasts, or Spotify.

If you want to host a screening for your community, contact us!

For screenings in Mexico - contact the Mexico distributors here.

If you want to watch it individually - rent it here.